Buying your way to Net Zero.

The murky market for global carbon credits.

– Melinda White, May 2023

In the process of working through our ESG scorecard updates in the last 6 months we have noticed a number of our portfolio companies announcing early achievement of net-zero targets via purchase of carbon credits.

We wanted to understand this in a bit more depth to ensure that:

- Companies are still reporting gross emissions (emissions haven’t been masked by carbon credit purchases)

- We understand the voluntary carbon credit market in more depth so that we can make informed judgements about the veracity of the net-zero target achievement.

- Where money is being spent on offsets, what the quality of those carbon credits are.

Our working thesis going into this project was that, given the lack of a globally regulated market with legislated enforcement (or local legislation around voluntary carbon credit use and reporting for corporate entities), it was highly likely that not all carbon credits were created equal. This opens the possibility that companies may attempt to achieve a “cheap” net-zero target by buying poorly verified international carbon credits. Price tells you everything: the fact that you can buy carbon credits on the international market for as little as $2/tn CO2e offset has to be a signal of something.

So first up, what are our portfolio companies actually buying?

Voluntary credits not compliance credits

Carbon credits have been in use for decades. The original carbon markets existed to facilitate mandatory (compliance) schemes used by companies and governments that are legally mandated to reduce or offset their emissions. However, in recent years, companies and individuals have been able to purchase carbon credits directly from projects via the voluntary carbon market.

Mandatory carbon markets are specific to states or countries in which the legislation has been enacted. They tend to be associated with cap-and-trade mechanisms that are designed to reduce carbon emissions from the heaviest emitters in an economy and financially penalise them if they don’t achieve reduction pathways.

The Voluntary carbon markets operate outside of compliance market legislation and enable companies and individuals to purchase carbon offsets on a voluntary basis with no intended use for compliance purposes. Any companies not covered by carbon reduction legislation are buying carbon offsets in the voluntary market.

In Australia the ACCU scheme (administered by the Clean Energy Finance Corporation) provides carbon credit units that can be used in government legislated compliance schemes or by voluntary market participants. Offshore voluntary markets are fragmented, global and non-legislated. Credits purchased in those markets cannot be used for compliance market offset.

Intangible asset. Complex creation process

We like to investigate new markets through a framework of first principal questions. So we ask ourselves a) what is the basic asset you’re buying followed by b) if the asset isn’t tangible, how many steps are involved in verifying the asset and how does the money get from buyer of asset to seller of asset.

Compared to the (equity) markets we operate in, the voluntary carbon credit market is a fragmented, emerging cottage industry. There’s limited standardization, limited regulation and a relatively opaque verification process (projects can be located anywhere and their auditors in-country).

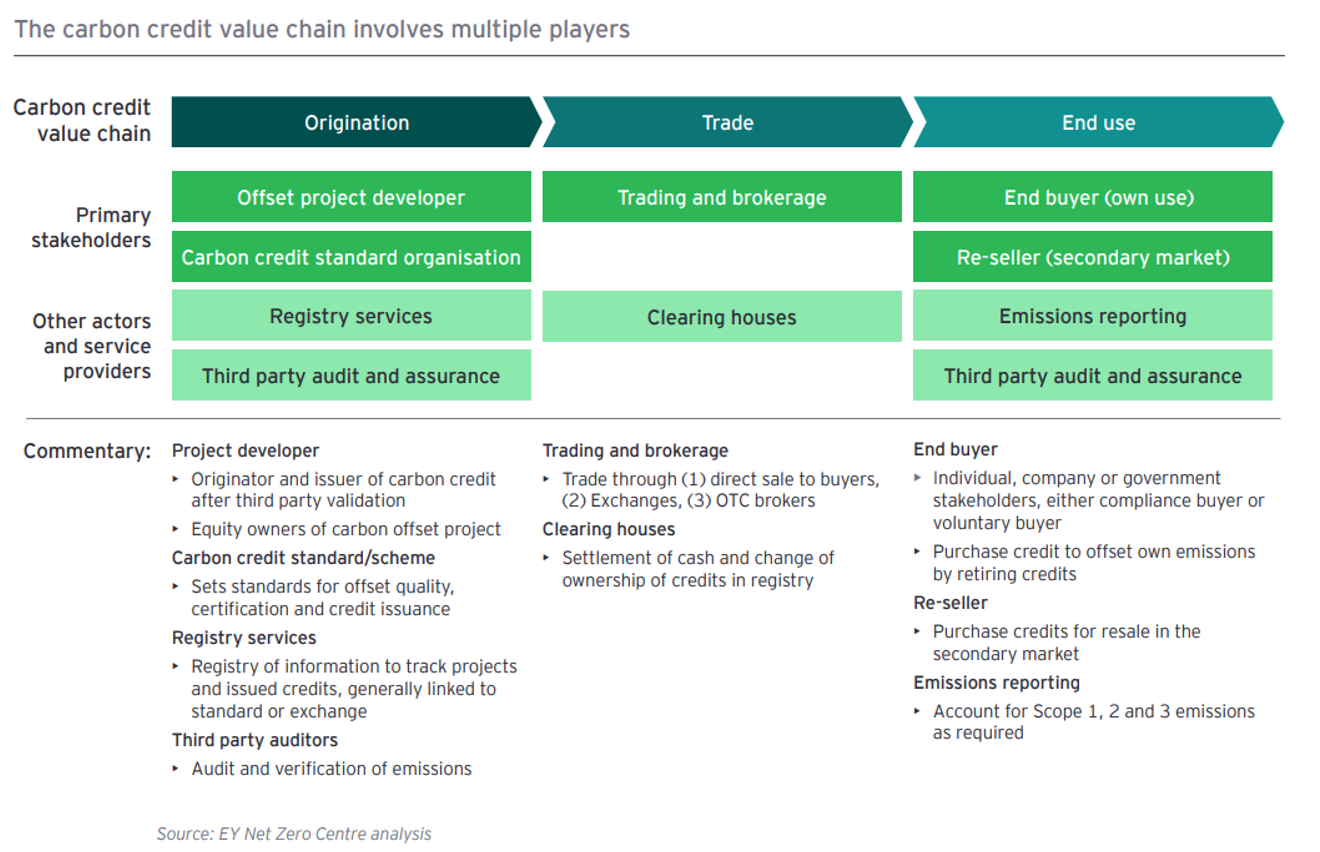

Let’s start with a meta-mental map. Carbon credit markets mirror most other markets in their overarching structure. The asset is originated, then it’s traded to the end user.

Source: EY Net Zero Centre (May 22)

That’s where the similarity to the markets we are familiar with end. Carbon credits are assets we can neither touch nor feel, but can be generated from underlying physical assets that are non-standard in nature. As a result, it’s at the point we delve into the question “what asset are we buying?” that the simple idea of “origination” becomes more complex. Because the asset (carbon credit) is intangible and derived from a different asset, there are multiple parties involved in just the origination step.

Carbon credit creation is complex

A carbon credit represents a reduction or removal of one tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) achieved by a project (Verra registry definition).

“Carbon credits themselves are abstract intangible things based on counterfactuals of things that you can’t actually see – emissions.”

(Verra Legal Counsel)

Credits are generated by projects which are originated by project proponents (originators). Projects can be located anywhere in the globe and take many forms. Some are paying communities not to cut down trees (avoided deforestation). Others are reducing CO2e via energy efficiency, renewable energy projects. Still others are implementing new methods for land or soil management. Most projects destined for the voluntary markets will be registered with one of the globally recognised registries (Verra, Gold Standard etc). These registries provide accreditation to third party auditors who verify and validate the project’s carbon emissions on behalf of the registries. The auditors are dispersed globally (in-country) and it’s not clear to us whether they are regulated in every country under standard legal and ethical frameworks. What we can see from reviewing the approved auditor lists is that there are many of them and they don’t appear to be associated with the big 4 global auditing firms.

The measurement methodology used by those auditors and project proponents to measure carbon emissions and reductions are approved by the registries (who are effectively creating and setting their own standards). On Verra alone there are 61 separate approved measurement standards. The registries don’t necessarily create the individual measurement methodologies. Instead, they are developed by project proponents, industry consultants and auditors working in concert; approved by Registries in the final stages.

We have reviewed some measurement methodology documents and have concluded that the methodologies are sufficiently complex as to make it virtually impossible for a generalist buyer to easily understand precisely what they’re buying.

Unlike accounting, there are no globally recognized qualifications, ethical practice standards or frameworks that the practitioners in the industry are working to. We think the industry has probably been given the benefit of the doubt for a long time given some participation of NGO’s in the industry and the assumption that anything environmental must be intrinsically operating to a higher ethical standard than anything motivated by capitalistic goals. However, as the market grows in size financially, we think there will need to be better separation of standard setting, registration, oversight and auditors to protect against bad-actors.

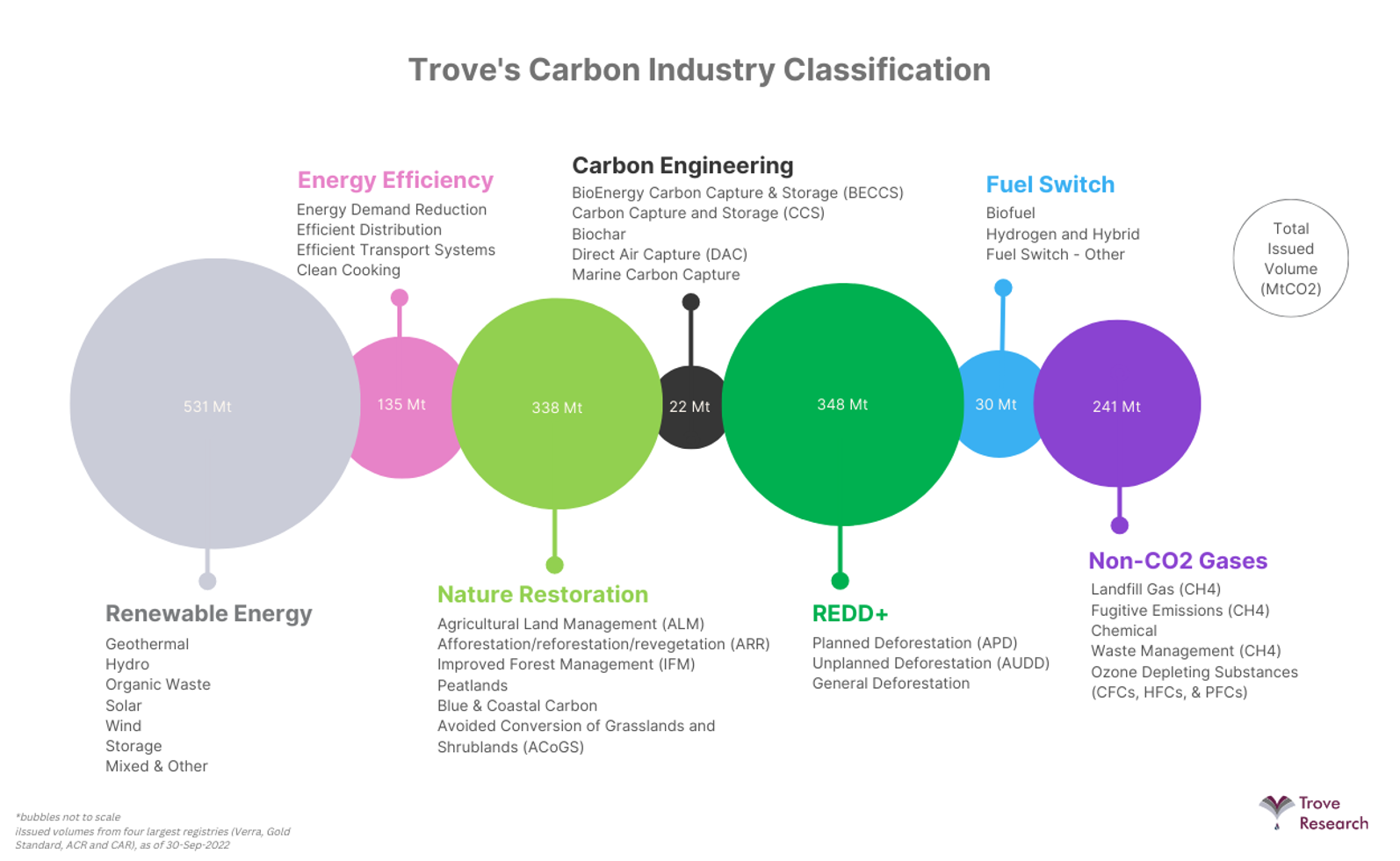

Seven broad groups of project types help to navigate market structure and sources of integrity issues

Because the basic asset in the carbon credit market is (unfortunately) not standard, there are a number of sub-classes of credits, all of which are different and have varying degrees of de-carbonisation credibility. We find Trove Intelligence’s classification (below) easy to understand and granular enough to provide some rigour to the credit sub-class framework.

Trove Intelligence divide credit sub-classes into 7 large categories. Trove captures data on 4,000 registered projects and 2,600 pipeline projects across 4 major credit registries and several smaller registries. The 3 biggest sources of credits today are Renewable Energy, Nature restoration and REDD+ projects. Emerging sources of credits are in fuel switch, carbon engineering and energy efficiency.

Source: Trove research intelligence (Mar 23)

Source: Trove research intelligence (Mar 23)

Most of the categories depicted above are relatively intuitive, but the REDD+ sub-credit stream is large and worth calling out as it’s one of the sub-classes where methodology really matters.

REDD+ projects are typically avoided deforestation in developing countries and are often initiated and administered at a national level. The “plus” in REDD+ refers to the role of conservation, sustainable management of forests and enhancement of forest carbon stocks in project countries. Theoretically the credits pay communities to stop a negative trajectory of deforestation and therefore have a positive impact on the current global warming trajectory. However, developing country communities have land requirements to support economic growth that may just be pushed elsewhere. It’s important to understand whether a project has caused agriculture or other activities to shift to a new location. Although this is supposed to be evaluated when the project is validated, the most recent industry scandal was a 9 month investigation by the Guardian and German investigative reporters on the weakness in underlying methodologies used to verify REDD+ projects[1].

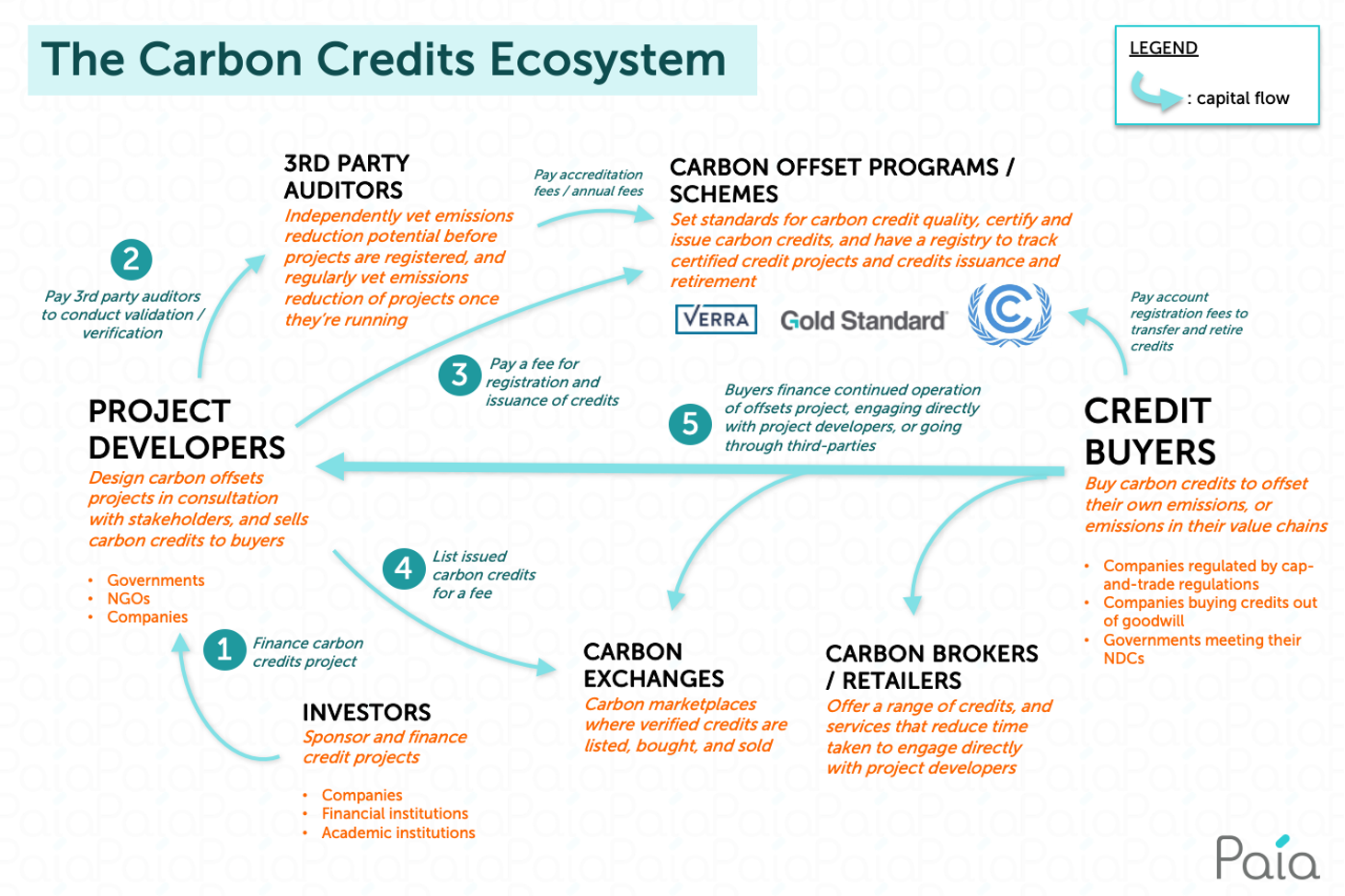

Transacting is still over-the-counter but registries do ensure double-counting is less likely

Once a carbon credit is created (originated), the process of transacting with a potential buyer is also relatively complicated. This is still largely an over-the-counter market and the larger registries don’t all allow buyers to transact directly with the registry. Transactions can be handled entirely through a broker, or initiated by a broker but contracted directly with a project proponent.

Ownership and clearing is also more complicated than traditional markets. Registries currently operate like walled gardens. Both sides of a transaction must have an account open with a registry to be able to transfer ownership between the two. Credits owned at one registry can’t be transferred to another (limited inter-operability). Account opening with registries isn’t necessarily simple, further restricting access to the market.

Source: Paia consulting (Jul 21)

Retirement of credit ownership in the voluntary market is also voluntary. Corporates who are claiming offsets each year are supposed to retire them through the registries, but we are unsure whether company auditors scrutinise the retirement transactions in the same way that they scrutinize other annual report claims. This is something we will investigate further.

Fragmentation, intrinsic non-standardisation lead to obvious questions around market integrity

If we take a look at the main components in the global voluntary market, we can quickly see that the ecosystem is complex to navigate and a generalist corporate buyer is unlikely to be in a position to make highly informed judgements around what they’re buying.

Project developers: many, fragmented, global

- 9 project registries

- 290 calculation methodologies (across 9 registries)

- 170 types of carbon credit projects (EcoSystem Marketplace)

- Fragmented validation and verification auditor base

- Fragmented broker ecosystem

Registries: Verra, Gold Standard, ACR, CAR, BioCarb, PuroEarth, Climate Forward, CDM, ART

Approved Methodologies: Verra (61), Gold Standard (36), ACR (18), BioCarb (8), PuroEarth (5), CDM (over 120), ART (1)

Although the voluntary market has the external appearance of an established market, but as you can see, when we look under the hood the non-standardization, fragmentation and self-policing that seems to be endemic in the industry leaves too many points at which credit integrity issues can creep in.

It’s no surprise then that there is increasingly strident criticism of the market. In Australia Professor Andrew Macintosh has labelled the Australian carbon market as a sham, claiming that most of the carbon credits approved didn’t represent real or new cuts in GHG emissions[2].

Offshore, the Guardian (in concert with Die Ziet and SourceMaterial and a range of academics who in some cases formerly worked for auditors or registries), published claims that 90% of the REDD+ carbon credits don’t represent real emission reductions[3].

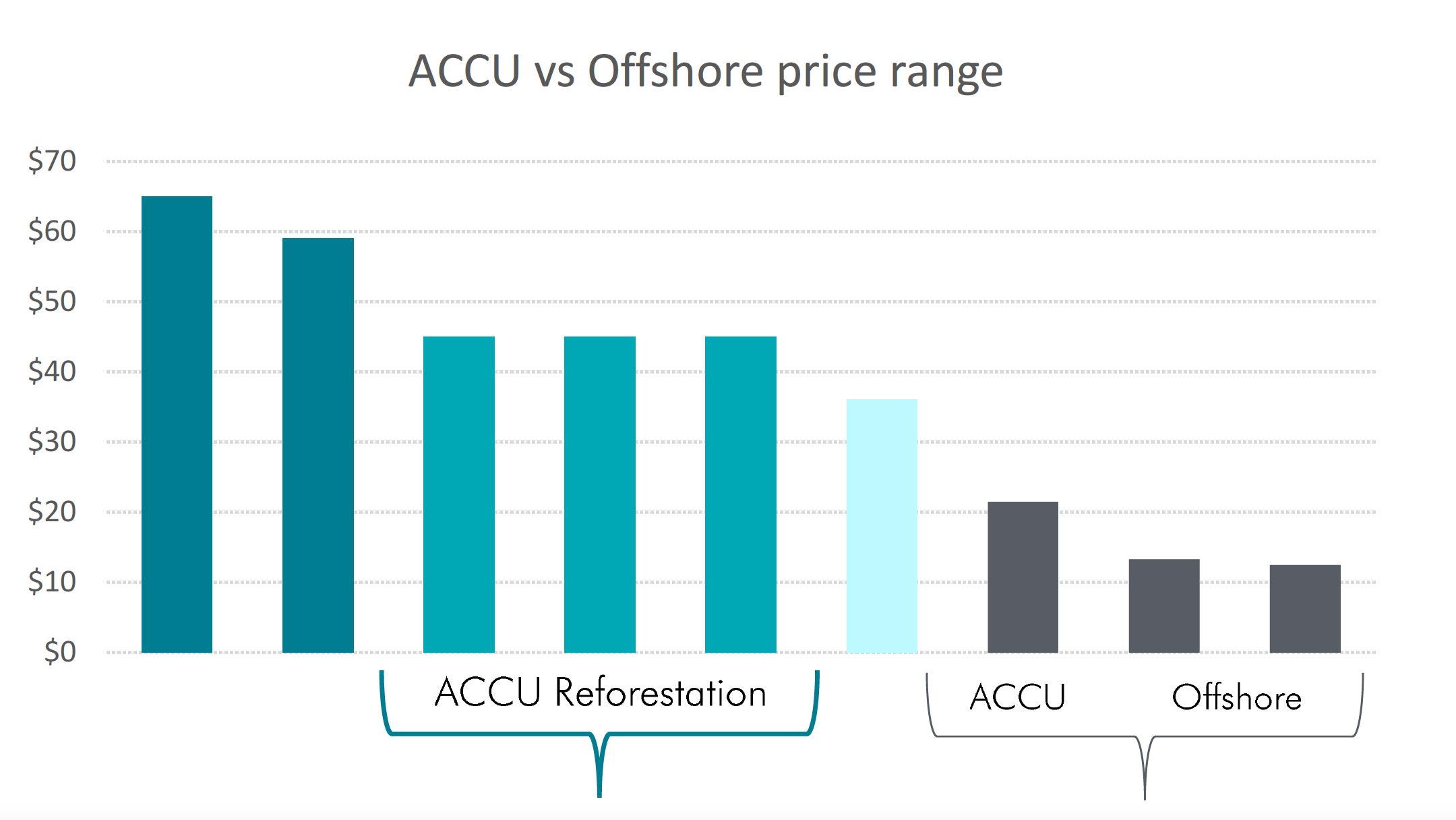

Market and project integrity issues lead to price dispersion

All of this leads us back to our original observation – that there is a big price dispersion between offshore credits and onshore credits. The following two charts show just how big that dispersion is.

The first chart shows a sample of prices from the highest priced (quality) ACCU project we could find through to 2 offshore REDD+ projects.

Source: Longwave Capital Partners (May 23)

Source: Longwave Capital Partners (May 23)

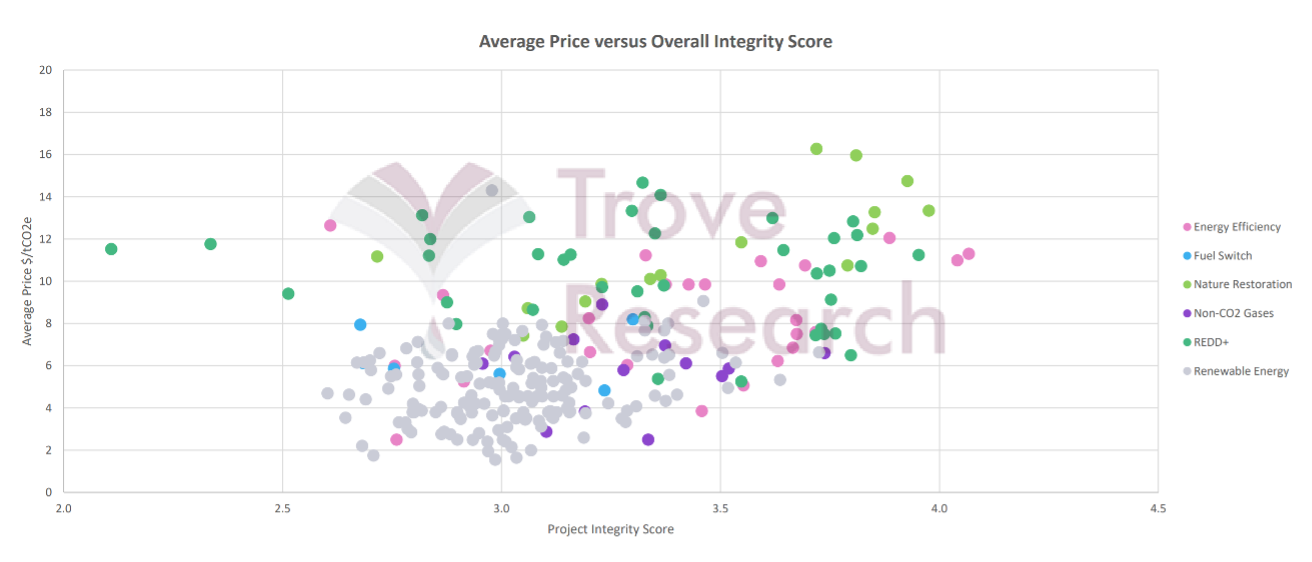

The second chart shows the price dispersion in the pure voluntary market as observed by Trove. Here they’ve colour coded the projects across their 7 sub-categories and shown price dispersion vs integrity score (Trove assessment). As you can see, the highest priced carbon credit in our observation set is $65/tn and the lowest priced is around $2/tn

Source: Trove Intelligence Research (Mar 23)

Source: Trove Intelligence Research (Mar 23)

Price dispersion between different types of credits is reflective of the issues around market and project integrity. From our perspective, we think the issues are:

- Complexity of calculation methodologies provides a level of opacity for buyers which immediately calls into question the ability of project proponents to game the system.

- Layering: the greater the number of intermediaries between origination and ownership, the lower trust the buyer should have in the integrity of the end-use asset.

- Self-creation of methodologies and standards: The process by which project proponents in concert with consultants can propose new methodologies and have them approved calls into question the rigour applied to calculation and measurement in the verification and validation stage of origination.

- Self-policing: There is no clear separation of registries and standard setters, nor separation between methodology creators and project proponents.

In the absence of voluntary market regulation and institutionalisation to ensure better market integrity, market participants have developed some rudimentary frameworks to judge project quality. The primary framework looks at registry, protocol and methodologies used, vintage, geography, co-benefits and additionality.

We’ve already looked at registry, protocol, methodology and to a lesser extent vintage and geography. Additionality speaks to whether a project is actually achieving the carbon reductions it claims to. In our mind, this is a further level of scrutiny on the calculation and measurement methodologies being used.

Co benefits (or non-carbon benefits) also impact credit prices. Projects can have flow on effects to local communities and potential human rights implications. In an Australian landscape, co-benefits are the additional positive environmental, socio-economic and First Nations outcomes delivered by carbon farming projects[4]. These carbon credits not only represent emission reduction or avoidance, but also contribute to improved biodiversity, or increased employment and economic opportunities or increased on-Country business opportunities for First Nations people, as well as supporting cultural and customary connections.

Given the increased scrutiny of the origination process and the number of initiatives underway to improve market integrity, we think a lot of these issues will ultimately be resolved. However, for the time being, we are going to engage with our portfolio companies to better understand the integrity of how they’re offsetting.

Portfolio Observations:

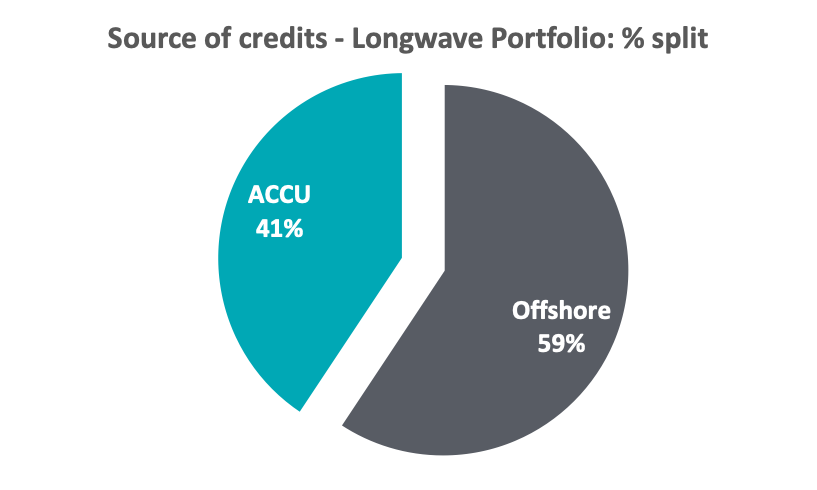

We have researched the carbon offsetting activity of the top 50 stocks in our portfolio (74% of our portfolio by weight). Of these, 16 stocks (25% by portfolio weight) disclose publicly that they purchase carbon offsets. The remaining 34 either don’t disclose or don’t purchase offsets. Of the portfolio stocks that do purchase offsets, almost 60% are purchasing offshore voluntary market credits.

Source: Longwave Capital Partners (May 23)

Source: Longwave Capital Partners (May 23)

Pleasingly, 9 of these (or almost 20% of the portfolio) disclose some information about the underlying projects they’re exposed to.

Engagement with portfolio investments

In the coming months we will be engaging with our portfolio companies to improve our understanding of their carbon offsetting programs. We will be seeking to understand whether companies know what they’re buying and how they assess quality. At the heart of this exercise is our desire to ensure that any shareholder capital being used in the name of climate change transition is, in-fact, working for that purpose. A flavour of the types of questions we will be asking, and we think investors need to know from their companies is below. They speak to how closely a company scrutinises its purchasing, understands the market its purchasing from and assesses the integrity of what they’re buying.

- How are you purchasing your carbon credits? (which broker, registry, exchange)?

- How much are you paying for your carbon credits?

- Are the underlying credits generated offshore or onshore?

- How many projects underlie your carbon credits?

- What project types do you preference when purchasing?

- Do you have additional criteria you’re looking for when you purchase?

- How do you validate the integrity of the project generating your credits?

We will report back on our findings later in 2023.

[1] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/jan/18/revealed-forest-carbon-offsets-biggest-provider-worthless-verra-aoe

[2] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/mar/23/australias-carbon-credit-scheme-largely-a-sham-says-whistleblower-who-tried-to-rein-it-in

[3] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/jan/18/revealed-forest-carbon-offsets-biggest-provider-worthless-verra-aoe

[4] https://www.qld.gov.au/environment/climate/climate-change/land-restoration-fund/co-benefits/overviewx

Disclaimer

This communication is prepared by Longwave Capital Partners (‘Longwave’) (ABN 17 629 034 902), a corporate authorised representative (No. 1269404) of Pinnacle Investment Management Limited (‘Pinnacle’) (ABN 66 109 659 109, AFSL 322140) as the investment manager of Longwave Australian Small Companies Fund (ARSN 630 979 449) (‘the Fund’). Pinnacle Fund Services Limited (‘PFSL’) (ABN 29 082 494 362, AFSL 238371) is the product issuer of the Fund. PFSL is not licensed to provide financial product advice. PFSL is a wholly-owned subsidiary of the Pinnacle Investment Management Group Limited (‘Pinnacle’) (ABN 22 100 325 184). The Product Disclosure Statement (‘PDS’) and Target Market Determination (‘TMD’) of the Fund are available via the links below. Any potential investor should consider the PDS and TMD before deciding whether to acquire, or continue to hold units in, the Fund.

Link to the Product Disclosure Statement: WHT9368AU

Link to the Target Market Determination: WHT9368AU

For historic TMD’s please contact Pinnacle client service Phone 1300 010 311 or Email service@pinnacleinvestment.com

This communication is for general information only. It is not intended as a securities recommendation or statement of opinion intended to influence a person or persons in making a decision in relation to investment. It has been prepared without taking account of any person’s objectives, financial situation or needs. Any persons relying on this information should obtain professional advice before doing so. Past performance is for illustrative purposes only and is not indicative of future performance.

Whilst Longwave, PFSL and Pinnacle believe the information contained in this communication is reliable, no warranty is given as to its accuracy, reliability or completeness and persons relying on this information do so at their own risk. Subject to any liability which cannot be excluded under the relevant laws, Longwave, PFSL and Pinnacle disclaim all liability to any person relying on the information contained in this communication in respect of any loss or damage (including consequential loss or damage), however caused, which may be suffered or arise directly or indirectly in respect of such information. This disclaimer extends to any entity that may distribute this communication.

Any opinions and forecasts reflect the judgment and assumptions of Longwave and its representatives on the basis of information available as at the date of publication and may later change without notice. Any projections contained in this presentation are estimates only and may not be realised in the future. Unauthorised use, copying, distribution, replication, posting, transmitting, publication, display, or reproduction in whole or in part of the information contained in this communication is prohibited without obtaining prior written permission from Longwave. Pinnacle and its associates may have interests in financial products and may receive fees from companies referred to during this communication.

This may contain the trade names or trademarks of various third parties, and if so, any such use is solely for illustrative purposes only. All product and company names are trademarks™ or registered® trademarks of their respective holders. Use of them does not imply any affiliation with, endorsement by, or association of any kind between them and Longwave.